Members of the Drift-RMT team prepare to test their buoy at the Chase Ocean Engineering Lab.

Data collection buoys are essential for gathering information about the ocean and climate, but these devices can also be unreliable when their batteries die and turn into ocean debris.

Students at the UNH College of Engineering & Physical Sciences (CEPS) and the Peter T. Paul College of Business and Economics are collaborating to tackle this problem with Drift-RMT, a renewable ocean data collection device that uses wave motion for self-sustaining power.

The Drift-RMT team is one of six competing for a $15,000 prize and an opportunity to advance their business idea at this year’s Paul J. Holloway Prize Competition. For the Drift-RMT team, the Holloway Competition is the first part of a busy May ending at the Marine Energy Collegiate Competition (MECC) in Portland, Oregon.

The effort began as a senior capstone project for a group of engineering students across three majors in Kara Wittmann, Riley Desmarais and William Moore, who wanted to create a product that could compete at MECC. Paul College student Cameron Vose joined the team at the end of the fall semester to assist with creating Drift-RMT's business plan. Soon after, the team decided to also compete in the Holloway Competition.

Bottom (L to R): Kara Wittmann and Riley Desmarais.

“When I started with the team, the product's design was at the forefront of our collective team brain,” says Vose, a senior majoring in entrepreneurial studies. “Adding Holloway and its imminent deadlines made us think about the feasibility of our project and putting it out into the world.”

Ocean surface drifters collect data for climate modeling, severe weather prediction and ocean navigation. Most ocean data collection devices use 30-50 D cell alkaline batteries. When those batteries drain, the buoy shuts down and is no longer traceable, meaning the ones that aren’t retrieved become ocean debris, explains Moore.

In the encapsulated space where the D cell batteries would’ve been, the Drift-RMT buoy has a mechanical arm that rotates and creates electricity.

“Our goal is that with only two lithium-ion batteries, we can hold a charge and power all the necessary instruments on board, but our renewable aspect is that when the device swings, when the motion of the waves rocks it around, it will just continue to live on and still be able to be located and replaced if needed,” Moore says.

According to Moore, traditional drifters last about 18 months, but many die sooner. The Drift-RMT drifter is projected to last 4-6 years.

The National Oceanic and Atmosphere Administration’s (NOAA) global drifter program uses around 1,200 drifters. While the Drift-RMT drifter is expected to cost more to build, the team believes their device would save NOAA and other organizations significant money in replacement costs, provide more accurate data and cut down on ocean debris.

While Wittmann, Desmarais, Moore and Vose are leading the Holloway effort, the entire Drift-RMT team includes 12 students, and it has taken the unique backgrounds of each to bring the idea to life.

“We wanted to contribute in a new and impactful way,” Wittman says. "With many marine energy projects, you see people come into the market with these expansive, technologically demanding ideas. So, finding a robust design we could work on and get behind as a team was challenging and rewarding."

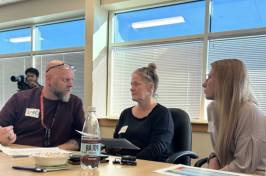

Based on the feedback they received from judges during the Bud Albin Challenge, the semifinal round of the Holloway Competition, the team is making some final adjustments to their business plan to be more intentional about the markets they want to target with the product and what data they should incorporate into their final presentations.

“Competing in Holloway has been a good opportunity for us to vet and validate our product while giving us more practice on pitching our idea,” Vose says.

While the results and feedback from the Holloway finals and MECC will play a role in Drift-RMT's future, the team is proud of what it has built and what its members have learned from each other, preparing for the competitions and building a business plan.

“I think the beauty of our team is that we do have so many interdisciplinary backgrounds. You have engineers, but within the engineers, you have ocean engineers that can provide different input than the environmental engineers working on the sustainability aspect,” Desmarais says. “You have the mechanical engineers working on the product's design to build and test. We all have this diverse engineering background, and then you have Cam, who brings the business perspective.”

Vose says the interdisciplinary collaboration has made his Holloway experience extra rewarding.

“I’ve learned a lot about engineering, and it’s been great to get outside of my business comfort zone and work on such a collaborative project,” Vose says. “Since we've come together for the competition, we've had to put on a lot of different hats. I've learned a lot about design and how the product works and I can articulate how it generates energy. I wouldn't have been able to do that two months ago. Will's an engineer, but he's helped me with the business plan."

Moore says the lessons from the effort will continue well past graduation.

“I see my future careers combining engineering and business. I always find myself leaning toward project engineering, and this competition has sent me further down that path and helped me realize that I want to have that marriage of disciplines in my career, which I think is a valuable thing to gain, especially in my final year of college.”

-

Written By:

Aaron Sanborn | Peter T. Paul College of Business and Economics | aaron.sanborn@hwfj-art.com