Amy Michael, assistant professor of anthropology and director of UNH’s Forensic Anthropology Identification and Recovery Lab, and true crime podcaster Laurah Norton (“The Fall Line”) have been joining forces to work on cold cases since 2018. Their latest collaboration is Norton’s first book, “Lay Them to Rest: On the Road with the Cold Case Investigators Who Identify the Nameless” (Hachette).

SPARK 2024 EDITION

Can robots help us see the ocean floor? How does sustainability boost the bottom line? Who was Ina Jane Doe? Spark, UNH’s annual research review, chronicles our researchers’ quest to ask — and answer — these questions, and many more. Find this story and more in the latest issue of Spark.

In it, Norton dives deep into forensic science, centering her narrative on solving the identity of Ina Jane Doe, a woman whose head was found in a rural Illinois park in 1993, with Michael and UNH students Kyana Burgess ’22 and Audrey Waterman ’21. The team’s investigation updated the original forensic sketch in collaboration with a forensic artist and used updated forensic methods that ultimately identified Susan Lund, a 25-year-old mother of three from Tennessee. Circumstances of her murder remain unsolved.

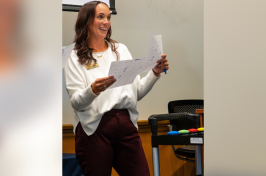

Michael talks about her collaboration on “Lay Them to Rest,” Ina Jane Doe/Susan Lund and assisting law enforcement identify John and Jane Does in New Hampshire and the nation.

Spark: What is forensic anthropology?

Amy Michael: Forensic anthropology is the application of skeletal biology, everything we know about the human skeleton, to the medical-legal process. A forensic anthropologist’s duty and obligation is to help identify unidentified people. Using methods that have been developed over the last 50 to 70 years, we can estimate age at death, we can estimate sex, we can estimate what we now call population affinity, or what we would colloquially call race. We can estimate height. Certain diseases and lifestyle factors may even manifest in the skeleton, leading us to interpret if the person had anemia, diabetes, arthritis and more.

Tell us about your collaboration with Laurah Norton.

I knew early on when I met Laurah that I wanted to work with her, and I felt like our skill sets were complementary. Laurah’s not a forensic osteologist like myself, and I am not a professional researcher in the way that is really needed in cold case work. She has a deep understanding of how archives and databases work. And we are both interested in rural cases that are in resource-poor jurisdictions.

How did you find your way to Ina Jane Doe?

I’m from central Illinois, a really rural small town. My family still lives there. I was 11 years old in 1993 when Ina Jane Doe was found and the circumstances of recovery always just kind of stuck with me.

I called the detective in charge of the case from B lot on campus. I dug out my central Illinois accent, and luckily I still have a Peoria, Illinois area code. Like a lot of law enforcement, he had not really had any contact with an anthropologist before. I explained to him that Laurah and I can bring these other dimensions, like skeletal reanalysis, like deep archival research, that can be parallel to law enforcement’s investigation.

You described a “national epidemic of unidentified remains,” with a likely outdated figure of 40,000 missing or unidentified persons in the U.S. Who are they, and why are you committed to identifying them?

I’m an anthropologist in part because people are complex and frustrating and fascinating. In forensic cases, we see a lot of intersecting factors like poverty, housing insecurity, unstable employment and lack of access to resources that often compound to make people vulnerable to violence.

A sad reality is that there are a lot of folks who go through their lives without any permanent or meaningful family or friendship ties. It’s unfortunate that sometimes Does are most cared about after death, by strangers like myself and Laurah and people online who want to know who they are and what their story was.

Forensic science is great and it has advanced leaps and bounds, but we still need the public to care about cold cases and unidentified people.

-

Compiled By:

Beth Potier | UNH Marketing | beth.potier@hwfj-art.com | 2-1566